Montgomery Carmichael was a British consular official and then consul in Livorno from 1890 to 1922. After retiring, he lived in Livorno until his death in 1936. He published his

Tuscan Towns, Tuscan Types and the Tuscan Tongue in 1901. This is the first of three posts from a chapter of the book describing his first arrival in a late 19th century Livorno.

He was the first acquaintance I made in Tuscany. I was leaning over the steamers side looking down at the swarm of boats that surrounded her. I knew no word of the Tuscan tongue, and was dimly wondering how I should get myself and my luggage ashore, and to what extent I should be fleeced in the process, when a brown, clear eye from a boat below caught mine full. It belonged to a gaunt creature in blue serge suit and boating cap, with the face of a Mephistopheles and the bearing and manners of an Archangel. And from his mouth there issued (O dulcet sound!)

English — as she is spoke, it is true — but English intelligible with an effort.

“Inglis gen'lman?” he queried with a polite grin.

I nodded, distrustfully perhaps.

“You come my boat, sair — ver good boat”

I reflected a moment. The Mephistophelean face in repose I distrusted profoundly; animated, it seemed to glow with an extra dose of the milk of human kindness. For better or for worse I would go in his boat.

“All right!” I shouted down.

“Au'ri! Au’ri!” he shouted back with great contentment; and in two minutes more he was beside me on the deck possessing himself of my hand-bags and excitedly bawling directions about my big trunks.

We landed without misadventure; a cab of my guide's approving sprung, as if by magic, from the quay-side. He openly prevented me giving a silver five-franc piece to the boatman, and made that angry, baffled worthy content himself with two. Then came the difficult question of tipping him. I fingered a variety of coins diffidently, and finally got ready the five-franc piece he had saved me.

“What hotel you go to, gen'lman?”

I told him, and tried surreptitiously to pass the five-franc piece upon him. He pushed my arm politely away, gently forced me into the cab, and in a trice was on the box beside the driver.

At the hotel he came up to my room, and patiently and gleefully unstrapped all my boxes. “No spend silver moneys here,” he said confidentially; “sell silver moneys and spend paper moneys. Me show Mister t'morr' mawnin'.” Again I fumbled for the five-franc piece, but he was already at the door bowing me a stately “goo'-bye, sair!” I never managed to pass that particular tip it was the first of a series of defeats which I sustained in attempts to reward loyal and valuable services.

First of three parts -

Second of three parts -

Third of three partsMontgomery Carmichael, “In Tuscany”

John Murray, London 1901See also:

In Tuscany -

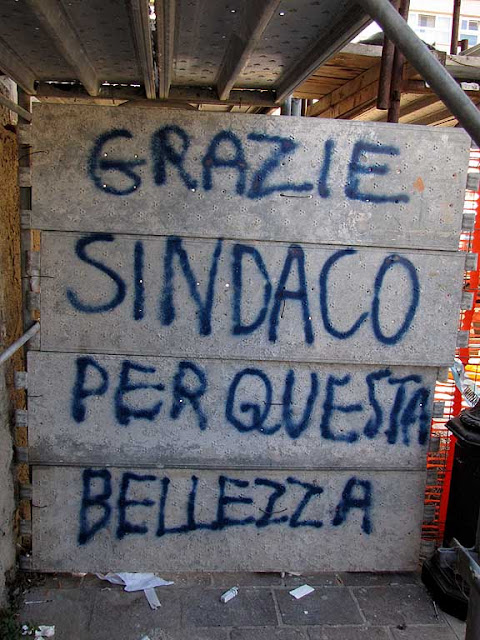

Leghorn “la Cara”

The 290 meter “Star Princess” was built in 2002 by Fincantieri in Monfalcone, Italy. A cigarette left burning on a balcony almost destroyed this ship in 2006, while en route from Grand Cayman to Montego Bay, after departing Fort Lauderdale.

The 290 meter “Star Princess” was built in 2002 by Fincantieri in Monfalcone, Italy. A cigarette left burning on a balcony almost destroyed this ship in 2006, while en route from Grand Cayman to Montego Bay, after departing Fort Lauderdale. The fire caused scorching damage in up to 150 cabins, and smoke damage in at least 100. A passenger died and thirteen others suffered from significant smoke inhalation.

The fire caused scorching damage in up to 150 cabins, and smoke damage in at least 100. A passenger died and thirteen others suffered from significant smoke inhalation. The ship was repaired and refitted at the Lloyd Werft shipyards in Bremerhaven, sprinklers were added to all balconies and the plastic furniture was replaced with non-combustible alternatives.

The ship was repaired and refitted at the Lloyd Werft shipyards in Bremerhaven, sprinklers were added to all balconies and the plastic furniture was replaced with non-combustible alternatives.